MESMER

: Towards a Playful Tangible Tool for Non-Verbal

Multi-Stakeholder Conversations

Ferran Altarriba Bertran

UC Santa Cruz

Santa Cruz, CA, US

ferranaltarriba@gmail.com

Ahmet Börütecene

Linköping University

Linköping, Sweden

ahmet.borutecene@liu.se

Oğuz ‘Oz’ Buruk

Tampere University

Tampere, Finland

oguz.buruk@tuni.fi

Mattia Thibault

Tampere University

Tampere, Finland

mattia.thibault@tuni.fi

Katherine Isbister

UC Santa Cruz

Santa Cruz, CA, US

katherine.isbister@ucsc.edu

ABSTRACT

In this paper we present MESMER, a work-in-progress tangible

conversation tool for playful design. Our work extends the

Otherworld Framework (OF) [7] for tangible tools by centering

specifically on play as a conversation topic. Here we unpack how

early experiments with OF motivated our work and describe the

current iteration of the MESMER tool, which comprises persona

cards, various boards, and a shared physical token. MESMER is

inspired by our findings from early trials with OF: performative

playful interaction promoted playful and divergent thinking;

embodied non-verbal communication led to shared insights, the

board’s contents and structure helped scaffold conversations, a

diversity of personas and narratives seemed desirable, and role-

playing personas encouraged multi-stakeholder empathy. Our

ongoing research aims to help designers and researchers to

facilitate engaging, fruitful and inspiring conversations where

diverse stakeholders can contribute to playful technology design.

CCS CONCEPTS

• Human-centered computing~Interaction design~Interaction

design concepts and methods

KEYWORDS

Play; Tangible Conversation Tools; Participatory Design.

ACM Reference format:

Ferran Altarriba Bertran, Ahmet Börütecene, Oğuz ‘Oz’ Buruk, Mattia

Thibault, and Katherine Isbister. 2020. MESMER: Towards a Playful

Tangible Tool for Non-Verbal Multi-Stakeholder Conversations. In

Extended Abstracts of the 2020 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human

Interaction in Play (CHI PLAY '20 EA). Nov. 2-4, 2020. Virtual Event, Canada.

ACM, NY, NY, USA, 5 pages. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3383668.3419872

1 Introduction

Many situations in our daily lives have an intrinsic playful

potential. The affordances of the objects we use, the features of our

social interactions and the framing of the situation itself are often

susceptible to having a “playful charge”. At any moment, the right

combination of events can spark play: a joke, a little teasing, or

just some uncontainable laughter. The emergence of play can

positively reframe how we relate with our environment. For this

reason, play has become a key topic in HCI, and researchers

investigate how to use its potential to enrich situations that have

traditionally been considered non-playful (e.g. [1][11][13][17]).

Works in this space often face a common challenge: how can we

design for play that enriches non-play activity without disrupting

it completely?

The Situated Play Design (SPD) [1] approach addresses this

challenge by focusing on chasing play potentials—i.e. "existing

manifestations of contextual play—to inspire play design. The

novelty of SPD is the proposal of building on forms of playful

engagement that emerge naturally in mundane situations—thereby

enriching, rather than disrupting, those situations by realizing

their playful potential.

While we believe that SPD points in the right direction, there still

are methodological gaps in this space [3]. Here we focus on one of

them: the lack of tools that help designers facilitate multi-stakeholder

conversations about people’s taste for play. Tangible tools have long

been used by designers and researchers to facilitate conversations.

Yet, they generally address conversation topics other than play

(e.g. innovation [9] or leadership [10]) and focus more on

stakeholders’ pragmatic needs rather than on their play(ful)

desires. Even those tools that use play to foster discussions usually

support design goals that are not ludic (e.g. [12][16]).

Facilitating discussions about a phenomenon as ephemeral and

elusive as play can be hard: we lack a robust language for the

aesthetic experience of play [14] and actionable mechanisms to

facilitate conversations about it. Because of that, we argue that we

could use new tangible conversation tools that focus directly on

play and playfulness and help designers to identify play potentials.

Permission to make digital or hard copies of part or all of this work for personal or

classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed

for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation

on the first page. Copyrights for third-party components of this work must be

honored. For all other uses, contact the Owner/Author.

CHI PLAY ’20 EA, November 2–4, 2020, Virtual Event, Canada.

© 2020 Copyright is held by the owner/author(s).

ACM ISBN 978-1-4503-7587-0/20/11

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3383668.3419872

MESMER, our work-in-progress tangible tool, responds to this

need.

2 From the Otherworld Framework to MESMER

MESMER is an extension of the Otherworld Framework (OF) for

tangible conversation tools [7]. OF repurposes the Ouija Board [6]

(Figure 1)—a popular game used for “connecting with the dead”—

as a resource for design. The game consists of a board with letters

and numbers and a token that moves around it—seemingly on its

own but in fact triggered by people’s subtle hand movements—

tracing messages “sent by spirits”. We hypothesized that such

embodied and non-verbal communication mechanism might add

value in design, enabling novel forms of collective exploration and

expression of nonconscious thoughts. Originally, OF did not target

play design per se; it was rather meant to support generic design

explorations. Yet, pilot trials showed that its underlying

mechanisms might be particularly useful in design projects

targeting play. Here we describe two trials that motivated our

decision to transform OF into a play-focused conversation tool. In

one of them, 4 participants (an engineer, a sociologist, a film

distribution coordinator, and a designer-facilitator) ideated

interactive garments by summoning the spirit of Jackson Pollock

through a custom board inspired by his art (Figure 2). In another

one, 3 participants (a semiotician, an engineer, and a designer-

facilitator, all Marie Curie Fellows) summoned the spirit of Marie

Curie through an emoji-based board to ideate playful wearables

(Figure 3). Here we highlight key findings from those trials that

motivate us to extend OF into a play-focused multi-stakeholder

conversation tool.

Finding 1 (F1): Performative playful interaction promoted

playful and divergent thinking. The emergent and

performative playfulness afforded by OF affected our ideation

process. As an intriguing and enigmatic activity, it enabled a

playful atmosphere where we felt safe to create and share

seemingly crazy ideas. For example, in the first study, discussions

after token movements generated keywords (e.g. dark, forest,

rabbit) that influenced subsequent questions and the ideation flow

(e.g. “He is in a dark forest with animals”), promoting lateral

thinking. An example is one of the ideas that came up in our

interactive garments brainstorming session: a pair of jeans made

of moss. Though we were not aware of moss’ properties, the OF

board enabled us to speculate on its possible uses and motivated

further exploration. We later found that moss has remarkable

liquid absorbing qualities, a relevant fact that may have been

ignored had we not allowed space for speculation. OF elicited the

intrinsic playfulness of the brainstorming conversation, brought

about experimentation and spontaneity, and helped us to diverge

from mainstream technology concepts—which we argue is a

Figure 1: The Ouija Board.

Figure 2: The first pilot study used a board inspired by

abstract art. Each circle corresponds to the spot where the

token (small jar in the left corner) stopped after each

question, and which the participants interpreted as

Pollock’s “answer”.

Figure 3: The second pilot study used a board featuring

emojis. Colored circles highlight the emojis where the

token stopped after each question, and which the

participants interpreted as Curie’s “answers”.

desirable move in playful design.

F2: Embodied non-verbal communication led to shared

insights. In both studies, we saw that the tool’s subtle, embodied,

ambiguous, and non-verbal communication mechanism could

balance negative power structures that emerge as people talk;

create a safe space where no one feels the urge to commit to ideas;

and dilute the sense of personal ownership to the benefit of

collective insights. Such conversation form might also disrupt

notions of expertise, e.g. mitigating people’s fear of being

perceived as stupid by others.

F3: The board’s contents and structure helped scaffold

conversations. The board’s contents helped to structure the

sessions and focus conversations, e.g. incorporating relevant

design concepts. For example, in the second study, we built on an

existing framework for playful wearables [8] to ask questions such

as: “How does the wearable help you to communicate: through

your body, using verbs, or symbols?”. That helped us to scaffold

the discussion and navigate between abstract and concrete ideas.

Future iterations of the tool might benefit from including different

boards that focus and scaffold different parts of the conversation.

F4: A diversity of personas and narratives seemed desirable.

In both studies we realized that while the original Ouija narrative

was compelling for some, it made others skeptical. A more flexible,

less mystical narrative might better accommodate a more diverse

set of participants, contexts, and design goals. We decided that

future iterations of the tool should also include realistic personas

in order to appeal to those who might feel uncomfortable with the

Ouija’s mysticism. We also determined that a clear explanation of

the rationale behind the board, its inspirational use, and the

facilitator’s role should be offered to participants.

F5: Role-playing personas encouraged multi-stakeholder

empathy. Summoning external figures created a shared lens for

discussion and enabled role-playing other people’s ideas. For

example, in the second study, pretending to be communicating

with Curie’s spirit affected our questions and subsequent

interpretation of “her answers”, e.g. assuming that she was a

straightforward and ironic woman, when the , and emojis

were highlighted, we concluded the session assuming Curie was

“hungry” and left riding her “horse”. Role-playing external

personas might help people empathize with the perspectives of

stakeholders who are not present, human and beyond. To better

encourage multi-stakeholder empathy, we decided that future

versions of the tool would use role-playing of non-present

personas as a central part of the activity.

3 The Work-in-Progress MESMER Tool

MESMER, the next iteration of our tool, extends the Otherworld

Framework by focusing conversations specifically on play and

playfulness. Building on the pilot trials findings, we kept the core

interaction mechanics behind OF (F1&2) but reframed the activity

to include non-spiritual themes (F4) and allow participants to role-

play any relevant stakeholder (F5). We also added structure to the

activity (F3) through a set of boards targeting diverse themes, e.g.

to focus directly on playfulness, one of the boards features play

design concepts. Below we describe the work-in-progress version

of MESMER.

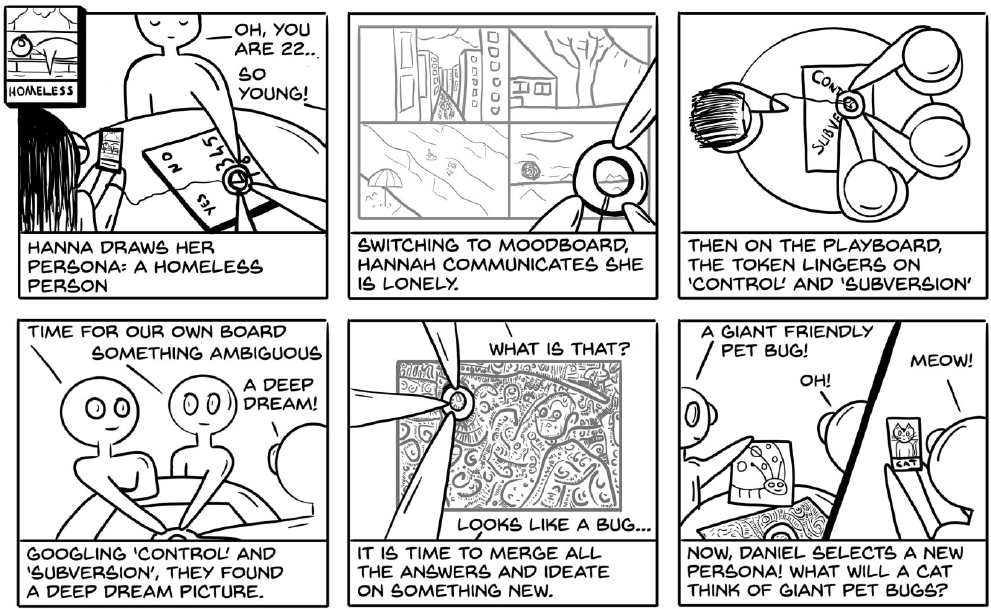

Let us imagine that a design researcher decides to use MESMER to

facilitate a multi-stakeholder conversation about the potential of

technology to playfully augment the public spaces of a city. The

conversation begins as one of the participants, the owner of a

popular coffee shop, pulls a card from a deck which assigns a

persona to her: a homeless person. Importantly, the cards feature

different personas, curated to be relevant to the targeted design

scenario. They include both humans, other living things (e.g. a

bird, or a tree), spirits of relevant historical characters (e.g. a

former mayor), and inanimate things (e.g. a light pole, or a

playground). Once the participant is assigned her new identity,

which will be visible to everyone, the other participants can start

interviewing her.

In the current version of the tool, conversations involve 4 phases,

each with its dedicated answer board—these phases can be seen in

the hypothetical MESMER session illustrated in Figure 4. The

conversation begins with a board featuring general prompts (e.g.

yes, no, maybe…) and letters; participants can ask questions to

familiarize themselves with the role-played persona (in this case, a

homeless person). Following, they move on to a mood board with

photos of city landscapes conveying diverse emotions; they can

use it to investigate the persona’s own experiences in, and ideas

about, the city. Next, participants use a board that includes a list of

playful experiences inspired by [4] and [5]; they can use it to

discuss the persona’s playful desires. The interview concludes with

a fourth board that is completely blank; participants can draw and

write on it to improvise custom questions and answers.

Importantly, in the interaction between interviewers and

interviewee, MESMER privileges non-verbal communication. To

get answers from the interviewee—in this case, the coffee shop

owner role-playing a homeless person—participants use their

fingertips to collaboratively move a token around the board,

reaching the available answer prompts. The interviewee can

influence those moves, e.g. by pulling a thread that is attached to

the token. We are in the process of experimenting with alternative

ways for interviewees to participate, with no conclusive results

yet. The activity is thus a game of empathizing with the

interviewee's thinking, understanding their subtle non-verbal cues,

and guessing an answer that satisfies all parties. If the interviewee

feels that their desires are not taken care of well enough, she can

pull the token outside of the board, in which case the interview

will be over, and another participant will be invited to draw a

persona card.

4 Conclusion and Future Work

MESMER is a work-in-progress tangible tool aimed at facilitating

multi-stakeholder conversations about play and playfulness.

Building on an existing method of our own work, the Otherworld

Framework, it uses subtle, embodied, non-verbal, and playful

interaction as the main communication form. Here we presented

our work-in-progress tool to open it up to the ideas of fellow

design researchers and play scholars and to learn how it may

support their work. Moving forward, we will iterate on the current

prototype through follow-up experiments: by inviting

stakeholders to use MESMER with us, and we will further develop

and refine both the tool and the underlying use protocol. Once we

determine that a robust version of MESMER is ready to be

evaluated, we will conduct a user study to assess its usefulness. To

do that, we will use the tool in some of our design research

projects to examine the extent to which it supported the projects’

design goals. To measure that, we will (1) video-record, and later

on study, participants’ behaviour in the MESMER sessions, and (2)

interview them about their perceptions of how using MESMER

enabled them to creatively contribute to the design work. Overall,

with this research, we work towards providing a tangible

conversation tool that empowers playful interaction designers and

researchers to facilitate fruitful, engaging, and inspiring

conversations where diverse stakeholders can contribute to the co-

design of playful technologies and experiences.

Acknowledgements

This publication has received funding from the European Union’s

Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the

Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 833731,

WEARTUAL and 793835, ReClaim projects.

Figure 4: A hypothetical MESMER session, part 1. A digital template for assembling the tool can be accessed at:

https://bit.ly/2Qa9YzX

REFERENCES

Ferran Altarriba Bertran, Elena Márquez Segura, and Katherine Isbister. 2020. [1]

Technology for Situated and Emergent Play: A Bridging Concept and Design

Agenda. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on Human Factors in

Computing Systems (CHI ’20). Association for Computing Machinery, New York,

NY, USA, 1–14. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1145/3313831.3376859

Ferran Altarriba Bertran, Elena Márquez Segura, Jared Duval, and Katherine [2]

Isbister. 2019. Chasing Play Potentials: Towards an Increasingly Situated and

Emergent Approach to Everyday Play Design. In Proceedings of the 2019 on

Designing Interactive Systems Conference (DIS ’19). Association for Computing

Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1265–1277. DOI:

https://doi.org/10.1145/3322276.3322325

Ferran Altarriba Bertran, Elena Márquez Segura, Jared Duval, and Katherine [3]

Isbister. 2019. Designing for Play that Permeates Everyday Life: Towards New

Methods for Situated Play Design. In Proceedings of the Halfway to the Future

Symposium 2019 (HTTF 2019). Association for Computing Machinery, New

York, NY, USA, Article 16, 1–4. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1145/3363384.3363400

Ferran Altarriba Bertran*, Danielle Wilde*, Ernő Berezvay and Katherine [4]

Isbister. 2019. Playful Human-Food Interaction Research: State of the Art and

Future Directions. In Proceedings of the 2019 Annual Symposium on Computer-

Human Interaction in Play (CHI Play '19). ACM, New York, NY, USA, 1001-1015.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1145/3322276.3322325 (* joint first-authors)

Juha Arrasvuori, Marion Boberg, Jussi Holopainen, Hannu Korhonen, Andrés [5]

Lucero, and Markus Montola. 2011. Applying the PLEX framework in designing

for playfulness. In Proceedings of the 2011 Conference on Designing Pleasurable

Products and Interfaces. ACM, 24

Elijah J. Bond. 1891. Ouija Board Game. Patent number US446054A. Accessed on [6]

March 3, 2020 at http://patents.google.com

Ahmet Börütecene and Oğuz ‘Oz’ Buruk. 2019. Otherworld: Ouija Board as a

[7]

Resource for Design. In Proceedings of the Halfway to the Future Symposium 2019

(HTTF 2019). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA,

Article 4, 1–4. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1145/3363384.3363388

Oğuz 'Oz' Buruk, Katherine Isbister, & Tess Tanenbaum. 2019. A design [8]

framework for playful wearables. In Proceedings of the 14th International

Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games (pp. 1-12).

Jacob Buur and Robb Mitchell. 2011. The business modeling lab. In Proceedings [9]

of the Participatory Innovation Conference. 368–373.

Simon Clatworthy, Robin Oorschot, and Berit Lindquister. 2014. How to get a [10]

leader to talk: Tangible objects for strategic conversations in service design. In

ServDes. 2014 Service Future; Proceedings of the fourth Service Design and Service

Innovation Conference; Lancaster University; United Kingdom; 9-11 April 2014.

Linköping University Electronic Press, 270–280.

William Gaver. 2002. Designing for homo ludens. I3 Magazine, 12(June), 2-6. [11]

Lego. n.d.. Lego Serious Play, Lego.com. Accessed on February 18th, 2020 at [12]

https://www.lego.com/en-us/seriousplay.

Elena Márquez Segura, Annika Waern, Luis Márquez Segura, and David López [13]

Recio. 2016. Playification: The PhySeEar case. In Proceedings of the 2016 Annual

Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play (CHI PLAY ’16). Association

for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 376–388.

DOI:https://doi.org/10.1145/2967934.2968099

Michael J Muller. 2009. Participatory design: the third space in HCI. In Human-[14]

computer interaction. CRC press, 181–202.

John Sharp and David Thomas. 2019. Fun, Taste, & Games: An Aesthetics of the [15]

Idle, Unproductive, and Otherwise Playful. MIT Press.

Ekim Tan. 2014. Negotiation and design for the self-organizing city: Gaming as a [16]

method for urban design. TU Delft

Steffen P. Walz & Sebastian Deterding (Eds.). 2015. The gameful world: [17]

Approaches, issues, applications. MIT Press.