navy

2019

social Media

Handbook

TABLE OF CONTENTS

1 INTRODUCTION

2 LEADERS

2 Overview of Today’s Online Landscape

2 Unofficial (Personal) Use of Social Media

3 Setting the Standard for Online Conduct

3 Reporting Incidents

4 Operations Security (OPSEC )

4 Political Activity

4 Endorsements

4 Impersonators

5 NAVY COMMUNICATORS

5 Overview of Today’s Online Landscape

6 Official Use of Social Media for Navy Commands

6 Policy

7 Deciding if Social Media Is Right for a Command

8 Alternatives

8 Strategy Development and Content Planning

9 Social Listening

10 Social Assessments

14 Crisis Communication: Casualties and Adverse

Incidents

15 Post information as it’s released

16 Correct the record

16 Analyze results

19 Account Security

20 Operations Security (OPSEC)

21 Political Activity and Endorsements

21 Online Advertising

21 Online Conduct

22 Impersonators

22 Bots

i

23 SAILORS

23 Online Conduct

23 Follow the UCMJ

24 Reporting Incidents

24 Political Activity

25 Cybersecurity

25 Cyberbullying

25 Operations Security (OPSEC)

26 Adverse Incidents

27 Private Groups

27 Endorsements

28 FAMILIES

28 Operations Security (OPSEC)

29 Adverse Incidents

29 Cybersecurity

30 Cyberbullying

31 OMBUDSMEN

31 Overview of Today’s Online Landscape

31 Best Practices to Support Command’s

Official Social Media Presence(s)

32 Cybersecurity

32 Operations Security (OPSEC)

33 Cyberbullying

34 Adverse Incidents

34 Private Groups

35 NAVY CIVILIANS

35 Cybersecurity

35 Operations Security (OPSEC)

36 Online Conduct

36 Political Activity

38 APPENDIX

ONLINE CONDUCT

ii

Mention of a commercial product or service in this document does not constitute official endorsement by the U.S. Navy,

the Department of Defense or the federal government.

iii

U.S. Navy Social Media Handbook

for Navy leaders, communicators, Sailors, families, ombudsmen and civilians

March 2019

1

WWW.NAVY.MIL/SOCIALMEDIA >> U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK

>> INTRODUCTION

Social media has revolutionized our lives, from the way we communicate and interact with the world to the content we

consume and the news we read. As a result, the way people get information has drastically changed, and the desire to

have real-time conversations with individuals, organizations and government entities has increased. This presents a

tremendous opportunity for everyone, from Sailors and families to Navy leaders and ombudsmen, to more effectively

communicate with one another and to share the Navy story more broadly.

Social media, when used effectively, presents unequaled opportunities for you to share our Navy’s story in an authentic,

transparent and rapid manner — while building richer, more substantive relationships with people you may not have

reached through traditional communication channels.

At the same time, the open, global nature of social media creates challenges, operational and cybersecurity considerations

and concerns regarding online conduct, including cyberbullying and harassment. Careful decisions on the best platforms

to use will ensure you convey the most relevant information as platforms rapidly adapt, age-out or emerge. Each section of

this handbook is tailored to the unique audience it’s serving: Navy leaders, communicators, Sailors, families, ombudsmen

and civilians.

Since social media is constantly evolving, we’ve included only enduring information that will remain relevant. We

encourage you to frequently visit http://www.navy.mil/socialmedia for the latest policy, guidelines, best practices,

standard operating procedures, training and other resources.

If you have questions or want to share feedback, contact the Navy Office of Information at 703-614-9154 or

navysocialmedia@navy.mil.

2

U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK >>

>> LEADERS

The Navy has an obligation to provide timely and accurate

information to the public; keep our Sailors, Department of

the Navy civilians and their families informed; and build

relationships with our communities. As a Navy leader, you’re a

crucial part of those communication efforts.

Social media, when used effectively, presents unequaled opportunities for you to share the Navy story in an authentic,

transparent and rapid manner while building richer, more substantive relationships with people you may not have reached

through traditional communication channels.

It’s important to remember that social media is only part of a command’s public affairs program. Navy leaders need to

work with their public affairs team to decide whether social media is appropriate for their command; not every command

needs to use social media. If you decide social media would benefit your command, evaluate each platform to determine

where your efforts will have the most impact; you don’t need to use every platform.

Overview of Today’s Online Landscape

Social media use is nearly universal among younger adults and is quickly growing among people over age 50. People

use it to consume news, make or strengthen connections, and engage in discussions and activism related to personal

interests. There are many different social media platforms, each with distinct use cases. Navy leaders need to work with

their public affairs team to focus their efforts on a social media platform that aligns with the command’s communication

objectives and that its targeted audiences use regularly.

According to a 2018 study by Pew Research Center, the percentage of adults who use at least one social media site

is as follows: 88 percent of 18- to 29-year-olds, 78 percent of 30- to 49-year-olds, 64 percent of 50- to 64-year-olds,

and 37 percent of people 65 and older. In total, nearly two-thirds of adults use social media. Specifically, 68 percent

use Facebook, 35 percent use Instagram and 24 percent use Twitter. Of the 68 percent of adults using Facebook, over

74 percent go onto the platform every day. Fewer users reported logging onto Instagram (58 percent) and Twitter (46

percent) daily.

Unofcial (Personal) Use of Social Media

Unofficial internet posts are posts published on any internet site by a Sailor or a Department of the Navy civilian in an

unofficial, personal capacity that include content about and/or related to the Navy or Sailors.

“Posts” includes but is not limited to personal comments, blogs, photographs, videos and graphics. “Internet sites”

includes but is not limited to social networking platforms, messaging apps, photo and video sharing apps and sites,

blogs, forums and websites with comment sections.

LEADERS

3

WWW.NAVY.MIL/SOCIALMEDIA >> U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK

If you’re expressing a personal opinion of any kind, it’s your responsibility to make clear you’re not speaking for the Navy

and that the stance is your own and not representative of the views of the Navy.

Setting the Standard for Online Conduct

As a Navy leader, you must lead by example. You must show your Sailors and Navy civilians that improper or inappropriate

online behavior is not tolerated and must be reported if experienced or witnessed. When it comes to your position as

command leadership, your conduct online should be no different from your conduct offline, and you should hold your

Sailors and civilians to that same standard.

If evidence of a violation of command policy, Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ) or civil law by one of your Sailors

or Navy civilians comes to your attention from social media, then you can act on it just as if it were witnessed in any other

public location. Additionally, pursuant to Navy regulations, you have an affirmative obligation to act on UCMJ offenses

you observe. This adds an ethical wrinkle to friending or following your subordinates; the key is for you to maintain the

same relationship with them online as you do at work and to be clear about that.

Sailors using social media are subject to the UCMJ and Navy regulations at all times, even when off duty. Commenting,

posting or linking to material that violates the UCMJ or Navy regulations may result in administrative or disciplinary

action, to include administrative separation, and may subject Navy civilians to appropriate disciplinary action.

Punitive action may include Articles 88, 89, 91, 92, 120b, 120c, 133 or 134 (General Article provisions for contempt,

disrespect, insubordination, indecent language, communicating a threat, solicitation to commit another offense and child

pornography offenses), as well as other articles, including Navy Regulations Article 1168, nonconsensual distribution or

broadcast of an intimate image.

Reporting Incidents

Anyone who experiences or witnesses incidents of improper online behavior should promptly report it.

Reports can be made to the chain of command via the Command Managed Equal Opportunity manager or Fleet and

Family Support office. Additional avenues for reporting include Equal Employment Opportunity offices, the Inspector

General, Sexual Assault Prevention and Response offices and the Naval Criminal Investigative Service (NCIS).

NCIS encourages anyone with knowledge of criminal activity to report it to his or her local NCIS field office directly or via

web or smartphone app at http://www.ncis.navy.mil/Pages/NCISTips.aspx.

4

U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK >>

Operations Security (OPSEC)

One of the best features of social media platforms is the ability to connect people from across the world in spontaneous

and interactive ways. Like most things we do as a Navy, social media can present OPSEC risks and challenges, but

they can be mitigated. Embrace the risks and challenges by reinforcing OPSEC rules, which are universal and should be

maintained online just as they are offline. Make sure your Sailors and Navy civilians as well as their families know that if

they wouldn’t say it, write it or type it, they shouldn’t post it on the internet.

OPSEC violations commonly occur when personnel share information with people they don’t know well or if their social

media accounts have loose privacy settings. As a Navy leader, carefully consider the level of detail used when posting

information anywhere on the internet. Reinforce OPSEC best practices, such as limiting the information your Sailors,

Navy civilians and families post about themselves, including names, addresses, birthdates, birthplaces, local towns,

schools, etc. It’s important to remember small details can be aggregated to reveal significant information that could

pose a threat. Work with your public affairs team to ensure best practices and standard operating procedures, addressed

in this handbook’s section for Navy communicators, are implemented.

Political Activity

Sailors may generally express their personal views about public issues and political candidates on internet sites, including

liking or following accounts of a political party or partisan candidate, campaign, group or cause. If the site explicitly or

indirectly identifies Sailors as on active duty (e.g., a title on LinkedIn or a Facebook profile photo), then the content

needs to clearly and prominently state that the views expressed are the Sailor’s own and not those of the U.S. Navy or

Department of Defense.

Sailors may not engage in any partisan political activity — such as posting direct links to a political party, campaign,

group or cause on social media — which is considered equivalent to distributing literature on behalf of those entities, and

is prohibited. Similarly, as a leader, you cannot suggest that others like, friend or follow a political party, campaign, group

or cause. Additional information is available at https://go.usa.gov/xEEqy.

Endorsements

Navy leaders must not officially endorse or appear to endorse any non-federal entity, event, product, service or enterprise,

including membership drives for organizations and fundraising activities. No Sailor may solicit gifts or prizes for

command events in any capacity — on duty, off duty or in a personal capacity.

Impersonators

Impostor accounts violate most social media platforms’ terms of service. The best offense is a good defense. Regularly

search for impostors and report them to the social media site.

The impersonation of a senior Navy official, such as a flag officer or a commanding officer, should also be reported to

the Navy Office of Information at 703-614-9154 and navysocialmedia@navy.mil.

LEADERS

5

WWW.NAVY.MIL/SOCIALMEDIA >> U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK

Social media, when used effectively, presents unequaled

opportunities for you to share our Navy’s story in an authentic,

transparent and rapid manner while building richer, more

substantive relationships with people you may not have

reached through traditional communication channels. Social

media has also led to new, creative ways and places to quickly

and directly tell your command’s story. Don’t be afraid to try

something different.

The Navy has an obligation to provide timely and accurate information to the public; keep Sailors, Department of the

Navy civilians and families informed; and build relationships with our communities.

It’s important to remember that social media is only part of a command’s public affairs program. Navy communicators

need to work with their command leadership to decide whether social media is appropriate for their command; not every

command needs to use social media. If you decide social media would benefit your command, evaluate each platform

to determine where your efforts will have the most impact; you don’t need to use every platform.

Your content — stories, photos, videos (b-roll and productions), infographics (still and video), blogs, etc. — is needed to

tell our Navy’s story. Submit released stories to the Navy.mil content management system and Navy Live blog proposals

to navysocialmedia@navy.mil. Follow current instructions on release of visual information and records management.

Finally, while this handbook will teach you best practices to tell our Navy’s story on social media, remember that there’s

no substitute for personally using social media to understand how to use it professionally.

Overview of Today’s Online Landscape

Social media use is nearly universal among younger adults and is quickly growing among people over age 50. People

use it to consume news, make or strengthen connections, and engage in discussions and activism related to personal

interests. There are many different social media platforms, each with distinct use cases.

As a Navy communicator, you need to focus your efforts on a social media platform that aligns with your command’s

communication objectives and that your targeted audiences use regularly.

According to a 2018 Pew Research Center study, the percentage of adults who use at least one social media site is

as follows: 88 percent of 18- to 29-year-olds, 78 percent of 30- to 49-year-olds, 64 percent of 50- to 64-year-olds, and

37 percent of people 65 and older. In total, nearly two-thirds of adults use social media. Specifically, 68 percent use

Facebook, 35 percent use Instagram and 24 percent use Twitter. Of the 68 percent of adults using Facebook, over 74

>> NAVY COMMUNICATORS

6

U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK >>

percent go onto the platform every day. Fewer users reported logging onto Instagram (58 percent) and Twitter (46

percent) daily.

Social media provides the ability to share news with your audience, with limitations. About two-thirds of American adults

(68 percent) say they at least occasionally get news on social media,. However, a majority (57 percent) say they expect

the news they see on social media to be largely inaccurate.

We know young Americans are very active on social media, but they’re less likely to show they’re engaged in content.

Though people age 18-29 are almost 20 percent more likely to use social media than people age 50-64, the older group is

4 percent more likely to share or repost a news story on social media and 10 percent more likely to comment on a news

story. These metrics should influence your command’s content strategies. If you want your messaging to resonate with

a younger audience, work on developing content that will engage younger users.

Teenagers use social media differently from other age groups. They’re less likely to use Facebook than older cohorts.

Roughly one-third of teens ages 13 to 17 say they visit Snapchat (35 percent) or YouTube (32 percent) most often, while

15 percent say the same of Instagram. Roughly half of teens (51 percent) say they use Facebook, and only 10 percent

say it’s their most-used online platform.

Social media use differs across different fleet areas of operation. In Asia, messaging apps, such as WeChat, LINE and

Facebook Messenger are more popular than traditional social media platforms. Similarly, in the Middle East, WhatsApp

is the most used social app, although Facebook and Instagram are also popular. Although Facebook is by far the most

popular social media platform across most of Europe, the Russian site VKontakte dominates in Russia, Belarus and

Kazakhstan.

Don’t feel that you must use multiple platforms. It’s far better to have one successful social media site than multiple

sites that aren’t used effectively.

Official Use of Social Media for Navy Commands

Navy social media sites are official representations of the Department of the Navy and must demonstrate professionalism

at all times. While third-party sites such as Facebook and Twitter are not owned by the DoN, there are guidelines for the

management of Navy social media accounts.

Policy

Department of Defense Instruction (DoDI) 8550.01, released Sept. 11, 2012, discusses the use of Internet-based

capabilities (IbCs), such as social media, and provides guidelines for their use. The instruction acknowledges IbCs are

integral to operations across the DoD. It also requires the NIPRNet be configured to provide access to IbCs across all DoD

components while balancing benefits and vulnerabilities. By definition, IbCs don’t include command or activity websites.

DoDI 8550.01 requires that all official social media presences be registered. Official Navy social media sites need to be

registered at http://www.navy.mil/socialmedia. SECNAVINST 5720.44C Change 1, Department of the Navy Public Affairs

Policy & Regulations, provides policy for the official and unofficial (personal) use of social media and for the content and

NAVY COMMUNICATORS

7

WWW.NAVY.MIL/SOCIALMEDIA >> U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK

administration of official Navy presences on social media, to include:

ADMINISTRATORS: Commands and activities shall designate administrators for official use of IbCs in writing.

The administrator is responsible for ensuring postings to the IbCs comply with content policy. Commands

permitting postings by others must ensure the site contains an approved user agreement delineating the types

of information unacceptable for posting to the site and must remove such unacceptable content. At a minimum,

the DoN’s current social media user agreement is required, available at http://www.navy.mil/socialmedia.

LOCAL PROCEDURES: Commands and activities must develop written local procedures for the approval and

release of all information posted on command and activity official use of IbCs.

SECURITY: Commands will actively monitor and evaluate official use of IbCs for compliance with security

requirements and for fraudulent or unacceptable use.

PRIMARY WEB PRESENCE: A command or activity IbC presence, including those on blog platforms, may not

serve as the DoN entity’s primary web presence and must link to the primary web presence, the command or

activity’s official website.

PROHIBITED CONTENT: Commands and activities shall not publish and shall prohibit content such as:

Personal attacks; vulgar, hateful, violent or racist language; slurs, stereotyping, hate speech, and other forms

of discrimination based on any race, color, religion, national origin, disability or sexual orientation.

Information that may engender threats to the security of Navy and Marine Corps operations or assets or to

the safety of DoN personnel and their families.

CORRECTIONS TO PREVIOUS POSTS: If correcting a previous post by another contributor on an IbC presence,

such posting is done in a respectful, clear and concise manner. Personal attacks are prohibited.

Deciding if Social Media Is Right for a Command

Social media is not a silver bullet for all your command’s communication needs. Not every command needs a social

media presence. It’s far better not to start a social media site than to use it ineffectively and abandon the site.

Before launching a social media presence, consider what you want to accomplish. What are your communication

objectives and how do they move your command closer to achieving its mission? Is the level of transparency required

in social media appropriate for your command and its mission? You also should consider your command’s priority

audiences and use the right social media platform to reach them. Do you want to communicate with your Sailors, Navy

civilians, command leadership, family members, the local community, a broader DoD audience, the American public or

another group altogether? Do you have the content and personnel — both now and long term — to routinely engage with

those audiences?

Additionally, if your command already has a social media presence, you should routinely ask yourself the above questions

to ensure it remains an effective communications tool. If it isn’t, take the opportunity to address the underlying issues

using the best practices in this handbook.

8

U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK >>

Alternatives

If your command wants to share information or content privately, social media is not your solution. Social media

is never the right venue for sharing sensitive information.

If you have sensitive information you want to limit to a specific group, consider one of the Navy’s private portals

that require a Common Access Card.

If the information or content is to be shared only with family members, consider using a dial-in family line or

conveying it through the command ombudsman, emails or family readiness group meetings.

If the information or content is to be shared with the local community, but the command is not subordinate to

Navy Installations Command, contact the base public affairs officer and/or the Navy region PAO.

If you have information or content that does not regularly change, consider the command’s public website.

Don’t create social media presences for individual missions, exercises and events. Instead, coordinate with

relevant commands and provide them content that is optimized — both written and visually.

Strategy Development and Content Planning

Social media is not a substitute for a public affairs program. As you decide how social media can support it, consider

your audience(s), goal, objectives and assessment method.

As public affairs plans are developed, discuss how to gather and produce content that is optimized — both written and

visually — for specific platforms based on your command’s social media strategy. A single event, such as a change-

of-command ceremony, can result in multiple products, such as a Navy.mil story, live tweets, a blog from the outgoing

and/or incoming commanding officer and a social media graphic with a quote — all from prepared remarks that can be

requested before the ceremony.

Once released, all Navy content is in the public domain and may not include any copyrighted material such as music,

photos, videos or graphics without the appropriate licensing.

In addition to deciding what you’ll create, discuss when and where you’ll share it. Not all your content needs to be shared

at once or on all your sites. For example, content shared on the Navy’s Twitter account is frequently not shared on

Facebook and vice versa. The Twitter account is a blend of news about the Navy and relevant trending content related

to the Navy that attracts new followers. Additionally, the posting frequency is different. Since Twitter is about what’s

happening in the moment, content is tweeted more often than posted on Facebook.

When content about a single topic is shared on Facebook and Twitter, it’s optimized for that platform. The tweet is

much shorter (due to Twitter’s 280-character limit) and includes relevant hashtags and mentions of other Twitter users.

Visually, the supporting imagery is edited by size and duration for each platform.

Once you’ve developed your content plan, update your content calendar. It can be tempting to connect, for example, a

Facebook account to a Twitter account so they automatically post to each other. Even though it will save you time, it’s not

an effective approach. Instead, it indicates you likely don’t have the personnel and content to sustain more than one site.

NAVY COMMUNICATORS

9

WWW.NAVY.MIL/SOCIALMEDIA >> U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK

Commands are responsible for official content posted on their social media. Like a press release or content posted

to a Navy website, information posted to an official social media presence must be approved by a release authority.

Contractors may help manage a social media presence, but they can’t serve as a spokesperson for the Navy. Therefore,

a Navy release authority must review and approve all content before a contractor posts it.

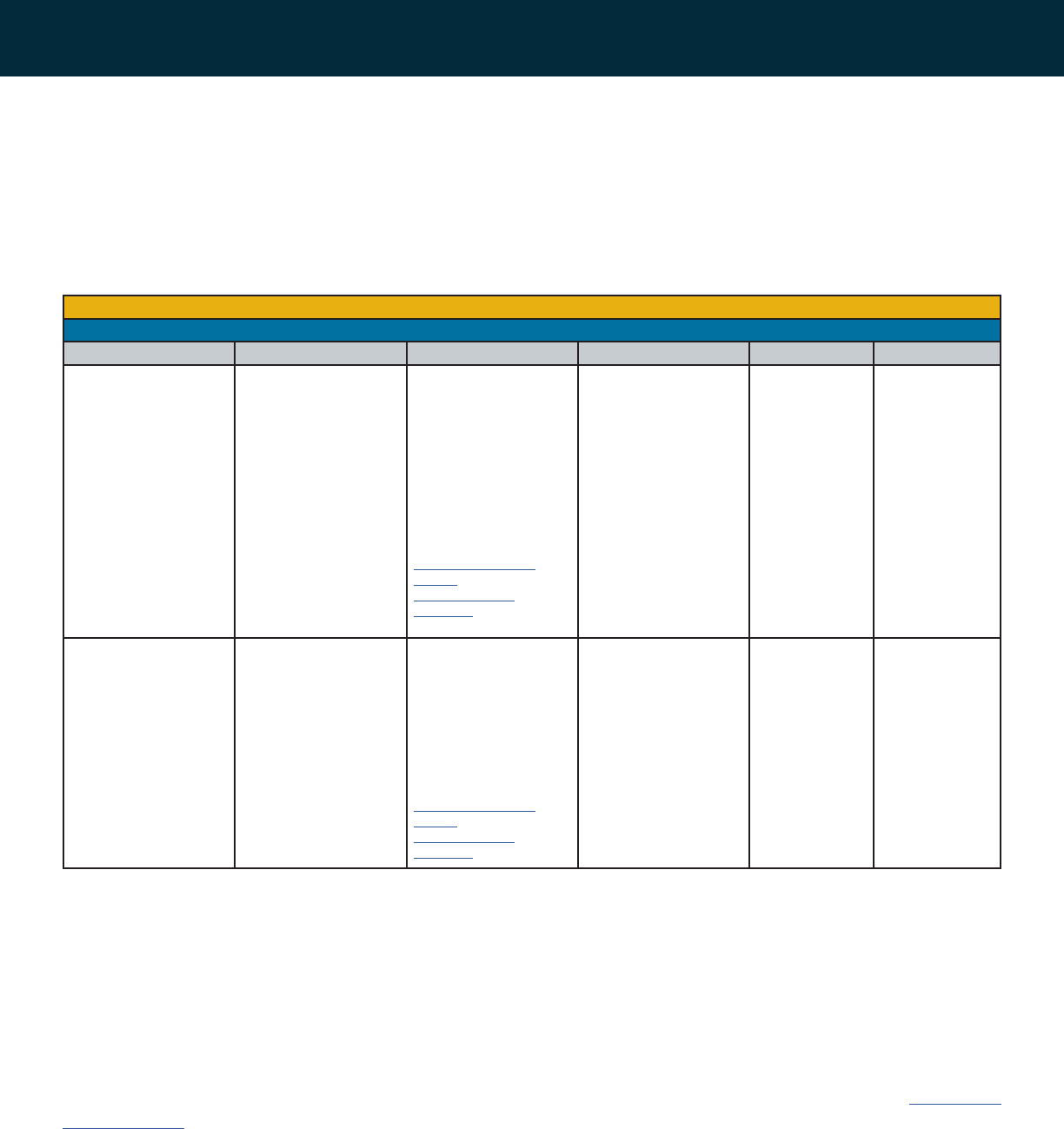

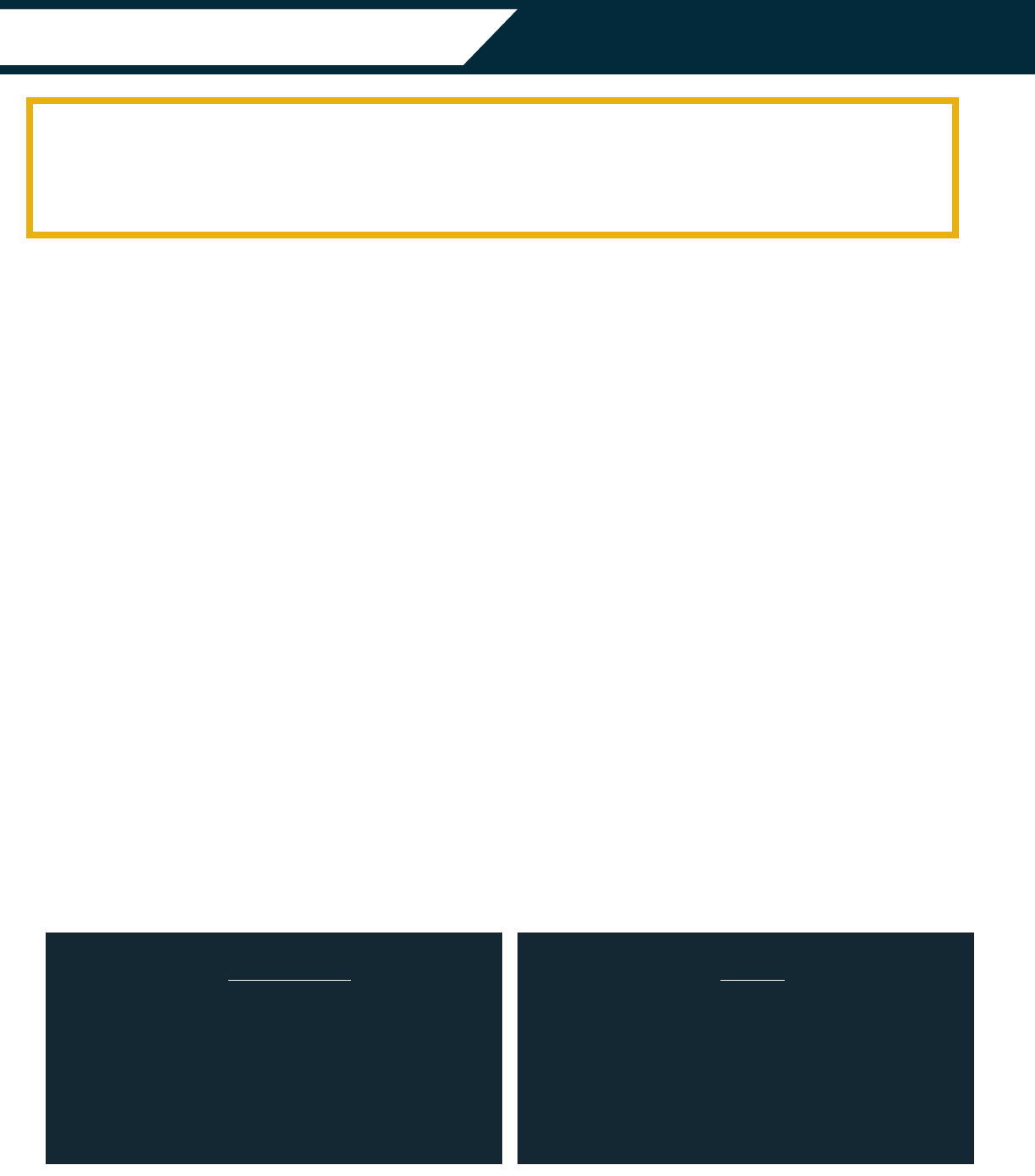

This is an example portion of CHINFO’s content calendar:

Social Listening

An important part of a social media strategy is keeping track of what’s being said about your command and understanding

the significance of specific social conversations. Social listening is different from social monitoring. Listening involves

both tracking mentions of a specific topic and extracting insights relevant to your strategy; listening can reveal sentiment

and trends.

While the most powerful social listening tools cost money, there are no-cost options. Search for free tools that work

across multiple platforms and allow users to monitor specific search terms in real time. TweetDeck (http://www.

tweetdeck.com) is a free Twitter tool that allows users to schedule tweets, view multiple timelines in one interface and

track specific hashtags in one location. TweetDeck allows you to set up columns in the main dashboard for certain

search terms or mentions of specific accounts.

Friday, February 15, 2019

Facebook

Time Type of content Text Imagery Line of effort Status

0935 Link This weekend, our

#USNavy’s newest

Independence-variant littoral

combat ship, the future

USS Tulsa (LCS 16), will

be commissioned in San

Francisco, expanding our

capacity. Be sure to watch

the ceremony live Saturday

at 1 p.m. (EST) / 10 a.m.

(PST) on our Facebook

page.

https://www.navy.mil/

submit/

display.asp?story_

id=108602

Link preview from story Equip Scheduled

(Approved by CM)

1217 Link During Exercise Citadel

Shield-Solid Curtain,

continental #USNavy

installations used realistic

training scenarios to

ensure their security forces

maintain a high level of

readiness. In Texas, those

scenarios turned from

training to reality.

https://www.navy.mil/

submit/

display.asp?story_

id=108629

Link preview from story Train Pending approval

10

U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK >>

Social Assessments

To ensure your social media efforts are achieving your aims, you should conduct periodic assessments. Each social

media site provides in-platform analytics. Tracking analytics weekly or monthly will reveal what type of content performs

best. In addition to the keeping track of the size of your audience, it’s important to see what content has the greatest

reach and receives the most engagement from your followers.

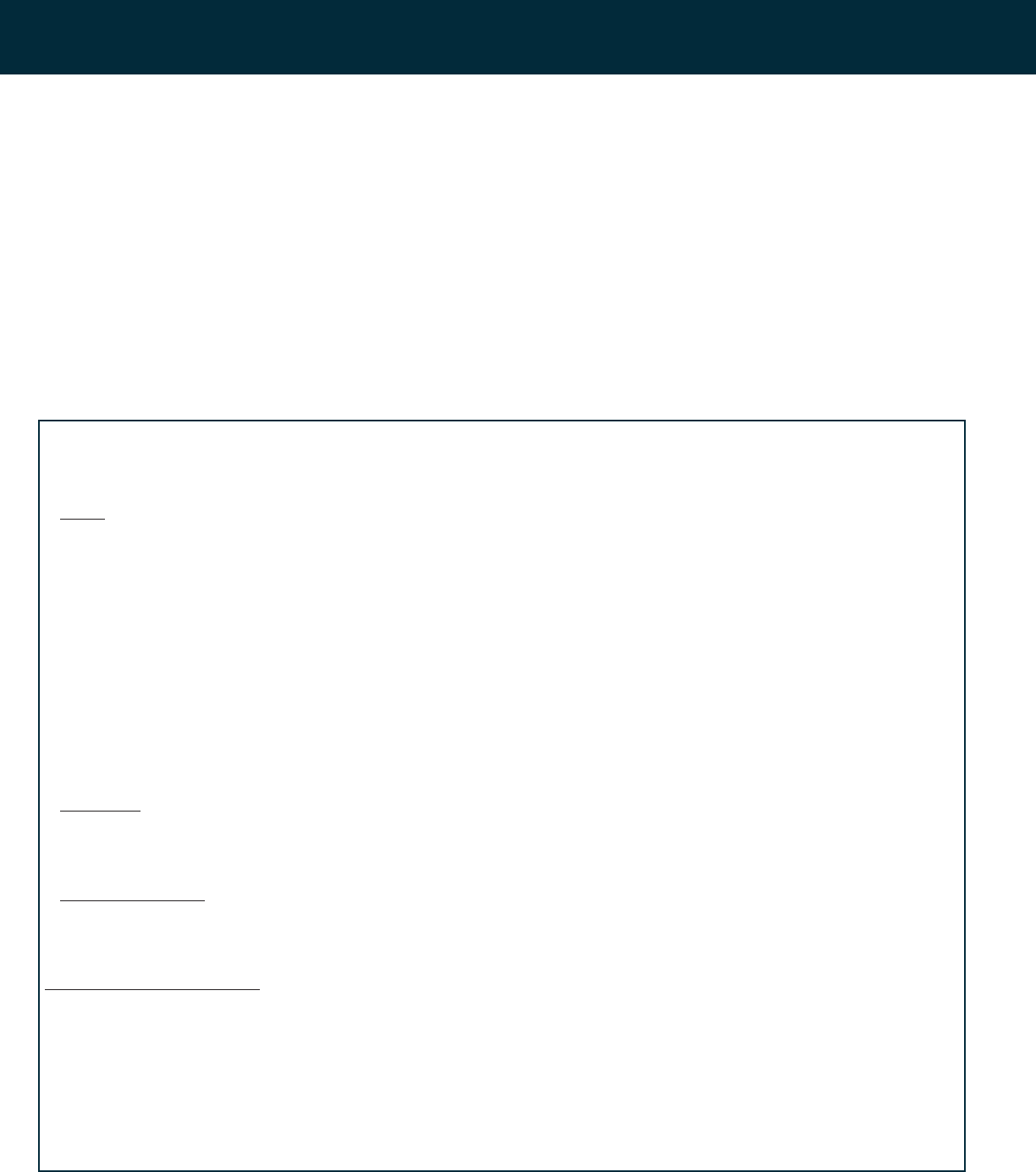

Assessments are also useful to evaluate one-off events and demonstrate to leadership the importance of social media

for communicating Navy messaging. See the following historical example assessing the impact of content related to

April 2018 strikes against chemical weapons capabilities in Syria. All the information in the report, which was captured

within the first 72 hours of content being posted, comes from analytics available in-platform on Facebook, Twitter and

YouTube.

SOCIAL MEDIA ASSESSMENT | SYRIA STRIKES

APRIL 17, 2018

BLUF: On April 13, 2018, combined U.S., French and British forces launched precision strikes against chemical

weapons capabilities in Syria to deter Syrian leader Bashar al-Assad from using banned chemical weapons. In the

72 hours that followed, CHINFO shared social media content related to the strikes on the Navy’s Facebook, Twitter

and YouTube accounts.

This content reached a large audience of Navy social media followers and users associated with those followers:

content related to the strikes was viewed over 800,000 times on Facebook, over 260,000 times on Twitter and over

200,000 times on YouTube.

On Facebook and Twitter, comments and replies generally reflected positive sentiment and expressed appreciation,

although users opposed to the strikes also left comments. The majority of comments left on YouTube videos were

in Russian and contained misinformation.

Summary: Social media posts related to the strikes reached a large audience and received generally positive

feedback. In total, related social media content was viewed over 1.2 million times and generated over 12,000

engagements. On YouTube, Russian actors appear to be engaged in a misinformation campaign.

Recommendation: Counter misinformation spread by Russian actors on YouTube. Consult with YouTube to

report the suspected misinformation campaign. Respond to English-language comments containing blatant

misinformation, and possibly remove Russian-language comments.

Total as of 12 p.m. April 17, 2018:

Facebook Impressions Earned via Related Content: 810,643

Facebook Accounts Reached via Related Content: 565,813

Facebook Engagements on Related Content: 8,629

Twitter Impressions Earned via Related Content: 260,550

Twitter Engagements on Related Content: 34,188

Twitter Retweets of Related Content: 538

YouTube Views on Related Content: 205,876

YouTube Comments on Related Content: 258

NAVY COMMUNICATORS

11

WWW.NAVY.MIL/SOCIALMEDIA >> U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK

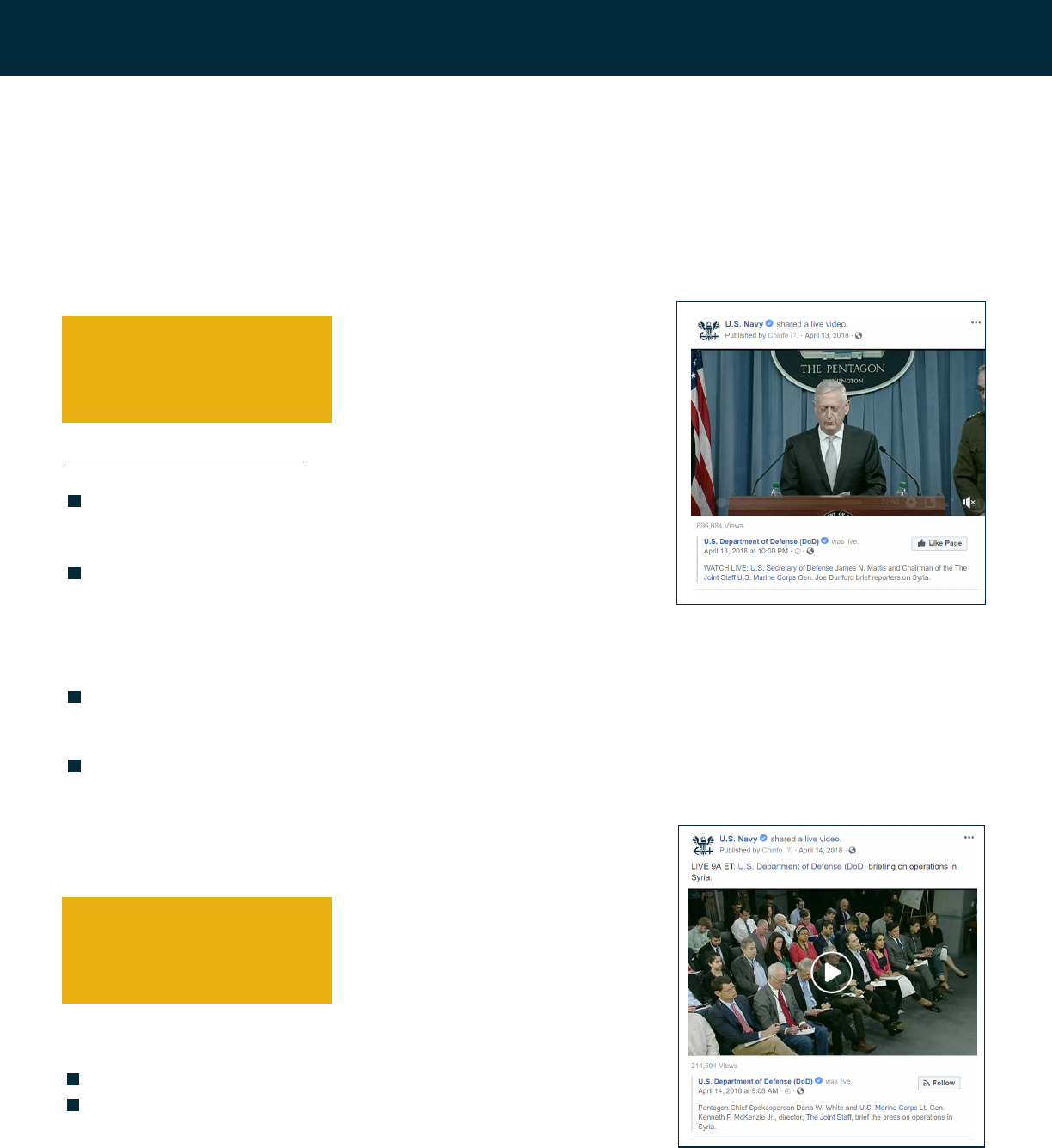

Facebook

Facebook content related to the strikes reached 565,813 users, received 810,643 impressions and generated 8,629

engagements. Comments were generally appreciative, although users opposed to the strikes also left comments.

1. SHARE: WATCH LIVE: SECDEF James N. Mattis and Chairman of the Joint Staff Gen. Joe Dunford brief reporters

on Syria

Impressions: 371,573

People reached: 251,148

Engagements: 4,896

Video views: 73,841

Theme of comments: Support

Example comments:

Anyone not ok with this attack and Trump’s decision. Look at your

kid or grandchild and imagine them in a gas attack. Sorry for being

so blunt but think about it. God bless our troops involved.

Be safe and show them WE are behind our President and our troops!!

Pray for them all!!

Theme of comments: Opposition

Example comments:

The United States has no place in this, should stay out of it all together not enough evidence to support any claims

the Syrian government did any such thing but then again since when did the US Government need proof to attack

another country - Love thy country hate thy government...

Trump wants to be known as a war president. A twitter war, a conventional war, a nuclear war, he doesn’t care,

as long as it’s a war. We have no business messing with Syria, or any other country for that matter.

2. SHARE: LIVE 9A ET: DoD briefing on operations in Syria

Impressions: 186,780

People reached: 129,032

Engagements: 1,260

Video views: 26,456

Theme of comments: Appreciation

Example comments:

Proud of my Navy and our allies

God bless our National Defense and the USA

YouTube Views on Related Content: 205,876

YouTube Comments on Related Content: 258

12

U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK >>

3. SPECIAL REPORT: INTERNATIONAL RESPONSE TO ASSAD CHEMICAL WEAPONS

Impressions: 252,290

People reached: 185,633

Engagements: 2,473

Theme of comments: Support

Example comments:

Well done Navy, and special thanks to our brothers in the

Submarine Service, who by necessity often patrol in thankless

secrecy. I believe I saw a Los Angeles class submarine was

instrumental in the strike, according to the public brief given less

than an hour ago. I’m afraid I didn’t catch the name of the boat

however. My thoughts and prayers are with our military, especially

our Navy. Thank you for your service past, present and future.

Theme of comments: Opposition

Example comments:

Chemical weapons use in Syria is not new. Why retaliate now? Because Trump needs a big distraction. I don’t

approve of Syrian leadership, however the time to have done this was years ago. This is just political grandstanding.

What happened to congressional approval? In 2013 he was all over Obama for the mere thought of getting

involved in Syria. Oh wait, that was when we had a real president not a dictator. Here is one of his many tweets

on the subject - “What will we get for bombing Syria besides more debt and a possible long term conflict? Obama

needs Congressional approval.

Twitter

Twitter content related to the strikes received 260,550 impressions and generated 3,418 engagements. The Navy’s

tweets on the strikes were retweeted 538 times. Replies were generally positive and expressed appreciation.

1. POTUS announces #SyriaStrikes

Impressions: 157,497

Total engagements: 2,194

Retweets: 320

Theme of replies: Appreciation

Example replies:

Stay safe.

We are praying for your safety and security

NAVY COMMUNICATORS

13

WWW.NAVY.MIL/SOCIALMEDIA >> U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK

2. #BREAKING: @DeptOfDefense briefing on #SyriaStrikes

Impressions: 103,053

Total engagements: 1,224

Retweets: 218

Theme of replies: Appreciation

Example replies:

This was an extraordinary briefing. Excellent

Praying for all our brave service men and women. Thank you for your sacrifice.

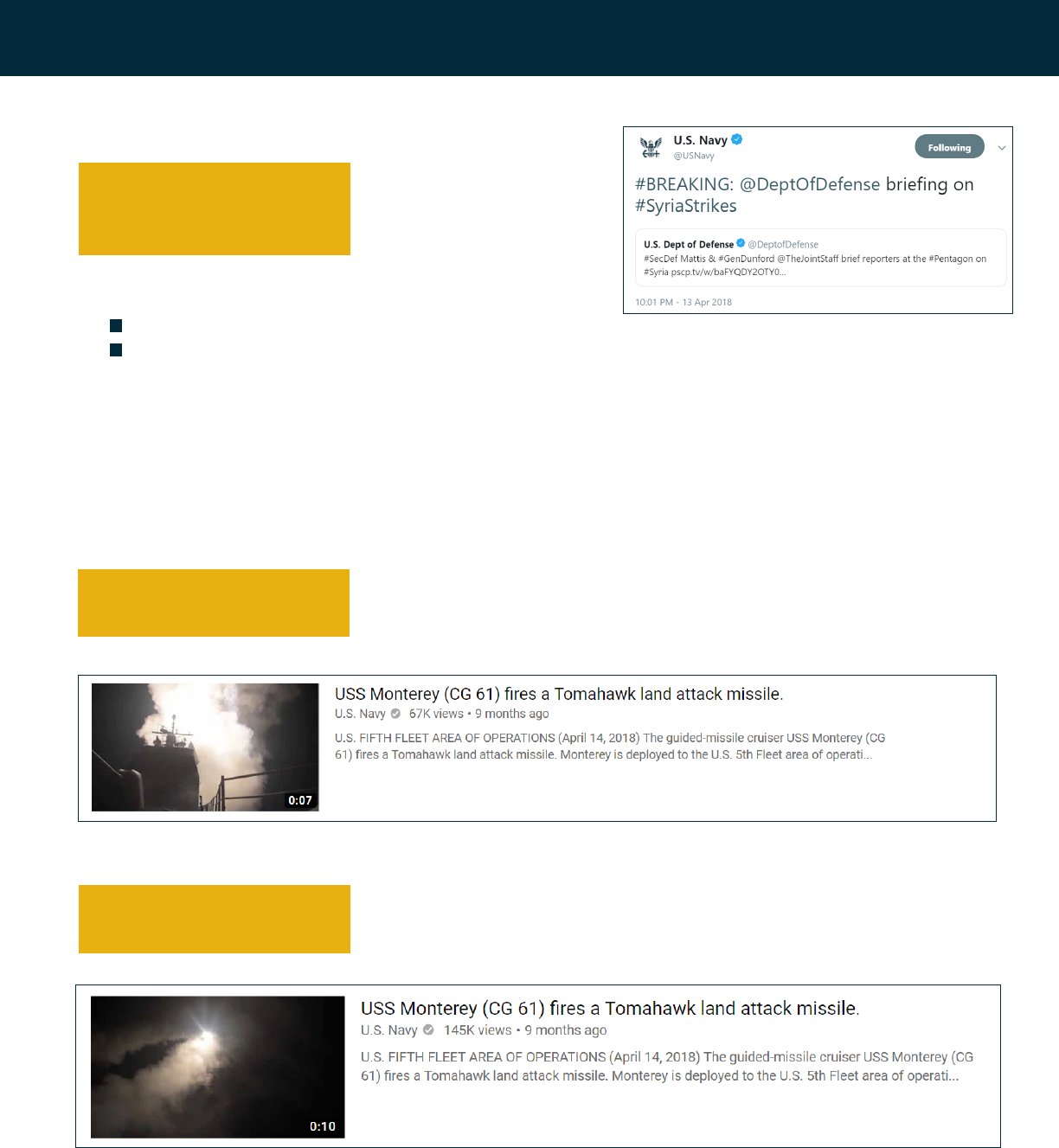

YouTube

YouTube videos of the strikes were viewed 205,876 times and received 258 comments. The majority of comments left

on the three videos were in Russian and contained misinformation.

1. USS Monterey (CG 61) fires a Tomahawk land attack missile.

Video views: 61,402

Comments: 65

2. USS Monterey (CG 61) fires a Tomahawk land attack missile.

Video views: 140,561

Comments: 161

14

U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK >>

Theme of comments: Misinformation

Example replies:

Where are the “smart” missiles. 103 rockets were produced. 71 missiles shot down. 17 missiles fell or exploded

in the desert. Only 15 rockets exploded near the target. These are very, very “stupid” missiles. this is the army

number one with the last place. America this attack cost $ 200 million, damage from missiles 0. it’s a shame.

Shity rockets. Almost all the missiles were shot down by the old Soviet air defense system xD

3. U.S. Navy Submarine Launches Tomahawk Missile

Video views: 3,913

Comments: 32

Crisis Communication: Casualties and Adverse Incidents

Social media is a major part of most people’s lives during good times and bad times. Using social media to communicate

with stakeholders during a crisis has proven effective due to its speed, reach and direct access. Social media distributes

official information and facilitates dialogue among the affected and interested parties.

If you can release information to the media, you can release the same information via your social media channels. As

you develop the crisis-communication portion of your public affairs guidance and plans, include possible social media

posts and tweets with your traditional holding statements.

Casualties

When personnel are killed, wounded or missing in action, it’s hard to control the flow of information distributed through

social media platforms. While it’s difficult to prepare for these situations, it’s important to know that social media can

play a role (good or bad).

The media may look at command, Sailor, DoN civilian and family members’ social media to get more information. It’s

important that privacy settings be regularly reviewed to be as restrictive as practical. It’s too late during a crisis.

It’s vitally important that all Sailors, DoN civilians, family members and friends know that the identity of a casualty

should not be discussed on social media until it’s been released. In accordance with DoDI 1300.18, DoD Personnel

Casualty Matters, Policies and Procedures, no casualty information on deceased military or DoD civilian personnel may

NAVY COMMUNICATORS

15

WWW.NAVY.MIL/SOCIALMEDIA >> U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK

be released to the media or the general public until 24 hours after notifying the next of kin regarding the casualty status

of the member. In the event of a multiple-loss incident, the start time for the 24-hour period commences upon the

notification of the last family member.

Adverse Incidents

The time to start using social media isn’t during a crisis. To build credibility, you need to establish a social media presence

before a crisis. A large social media following doesn’t happen overnight, so relax and execute your social media strategy.

The better you’re at providing good information and engaging your audience, the faster your following will grow.

The best course of action during a crisis is to leverage existing social media presences. If you have a regularly updated

channel of communication before a crisis, then your audiences will know where to find information online. Don’t make

your audience search for information. For example, if your command is preparing for severe weather, tell your audience

where they should go for the latest information.

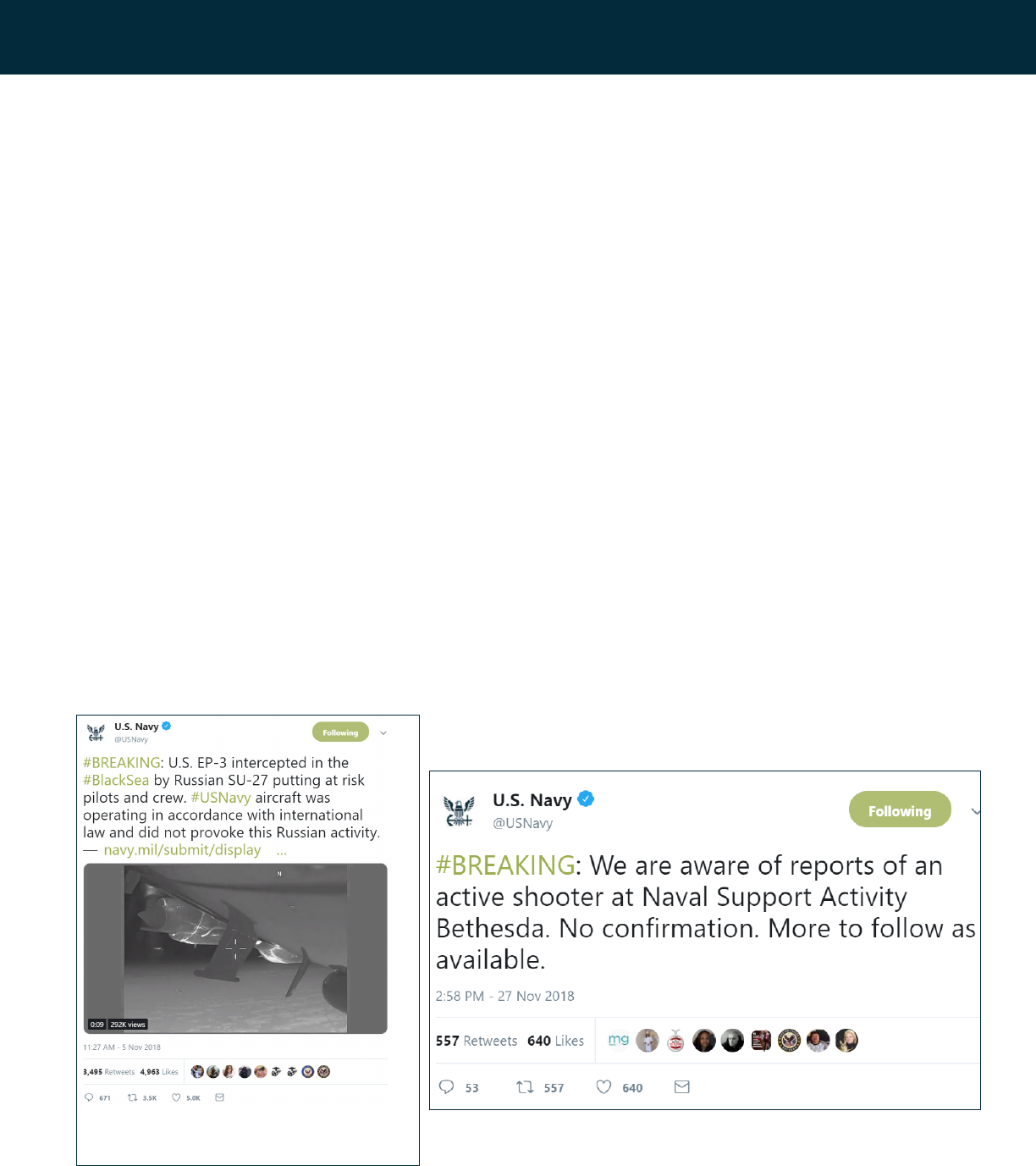

Post information as it’s released

Social media moves information quicker than ever, so when a crisis hits, don’t wait for a complete formal press release.

When you have information that’s released and confirmed, post it. You can always post additional information as it’s

released. If you expect you’ll provide updates, say so. Not posting timely updates during a crisis may damage the

command’s credibility.

While the below examples are from Twitter, the same principles apply to other social media platforms.

16

U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK >>

Correct the record

This example is a reminder to be prepared to respond to misinformation

and rumors before they become widespread.

Following media reports that the Navy was sending an “armada” of 12

ships to the Middle East, the Navy tweeted a correction.

If the Navy had not replied with a coordinated response, this inaccurate

news story would have gained traction. It would’ve been much more

difficult to correct additional media reports and the resulting

social media conversation.

Analyze results

Once the crisis is over, analyze what happened. Evaluate metrics and track user feedback. It’s important to evaluate how

a social media presence performs during a crisis so adjustments can be made for the future.

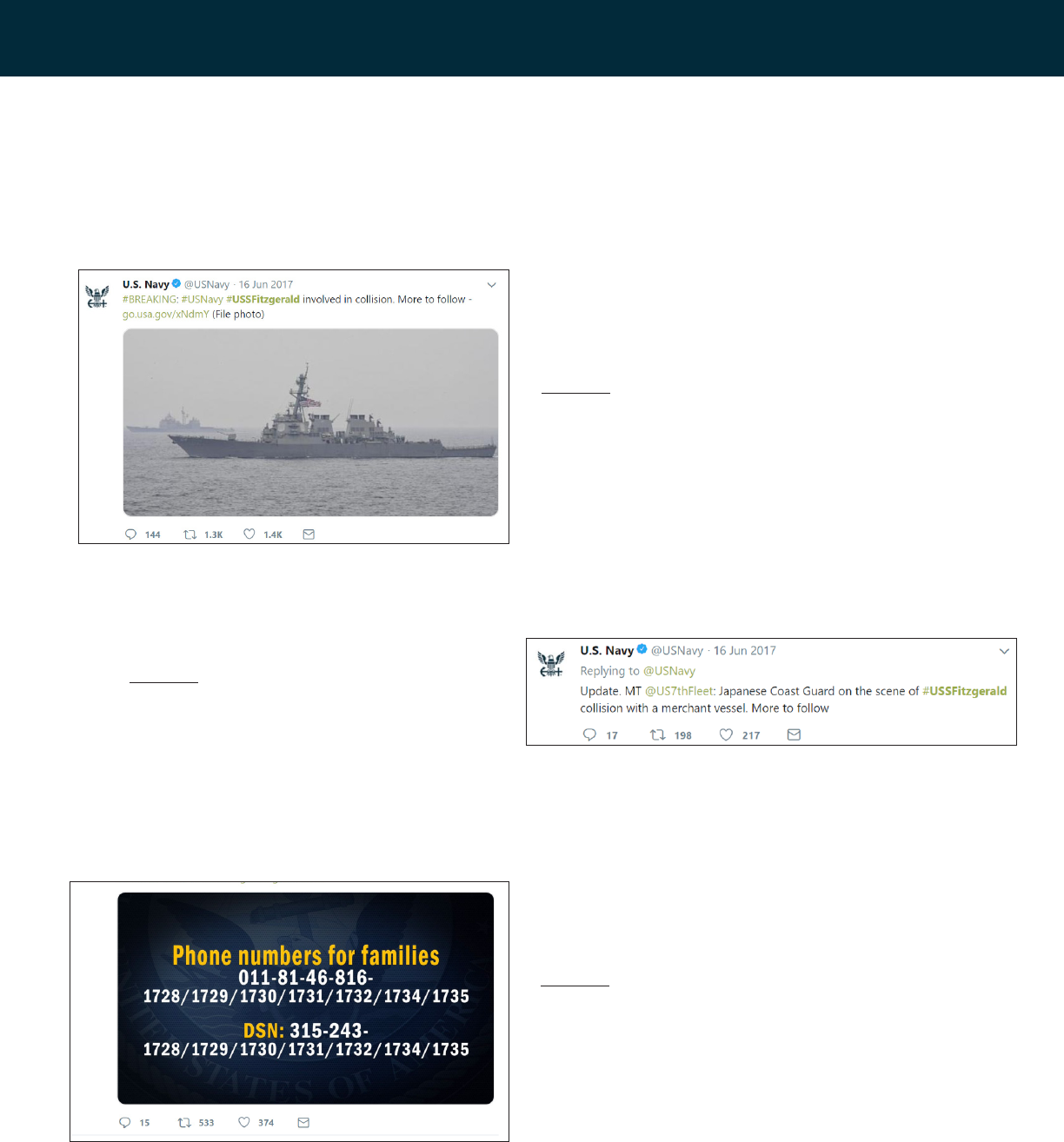

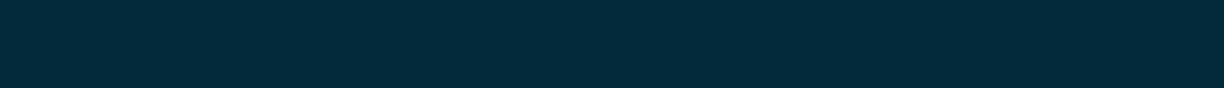

Case study: USS Fitzgerald and USS John S. McCain collisions

The Navy’s use of Twitter following the June 2017 USS Fitzgerald and MV ACX Crystal collision and after the August

2017 USS John S. McCain and Alnic MC collision provide examples of best practices for keeping the public up-to-date

during a fast-moving news situation.

Build relationships. Don’t wait for something big to happen to get familiar with the public affairs officer in charge

of media queries, build relationships on Twitter with your local media, know who your social media influencers are and

communicate with them often. If you wait until you need someone to get to know them, you’ve waited too long.

Have a well-trained team. Be comfortable using Twitter before a crisis. Even if you’re the Twitter guru on your

team, make sure the rest of your colleagues understand how to use the platform. For the Fitzgerald and McCain collisions,

CHINFO had three people dedicated to various Twitter-related tasks. So set up a training session, have your colleague sit

beside you when you draft tweets and recommend some reading. Make sure you have people in your office, other than

yourself, who you trust to tweet on behalf of your command. You never know when you’ll need the help.

Be able to react quickly. The first step in a crisis situation is confirmation. You may not know all the details, and

that’s okay, but the people involved and the media want information. The days of waiting for that perfectly polished press

release are over. News is happening, and it’s happening now.

Instead of waiting to release a statement until you have the full story, ask yourself, “What do I know now?” This is where

being a trusted adviser is critical. Talk to leadership and emphasize the need to get ahead of the press release with

confirmed and releasable facts, but remember speed does not replace the need for accuracy.

NAVY COMMUNICATORS

17

WWW.NAVY.MIL/SOCIALMEDIA >> U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK

For both events, we knew there was a collision, we knew the location and we knew about efforts to recover missing

Sailors. The ability to tweet that information once released — even before the full press release was complete — helped

to frame the story and controlled misinformation. Additionally, since we knew there would be frequent updates, we told

the media to monitor the Navy’s Twitter account for the latest information.

Tweet 1: Initial breaking news with link to Navy.mil

Tweet 2: Updates were shared as they became

available

Tweet 3: Resources for affected families were shared

as they became available

18

U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK >>

Sending tweets is only half your job. Twitter is complex. A lot is happening all the time, and it’s hard to keep up without

diligently monitoring. CHINFO has several established monitoring streams we check throughout the day, but in an

instance like the Fitzgerald and McCain collisions, they weren’t enough. Set up the following streams that you and your

team should monitor daily:

Mentions of your account’s handle (e.g., @USNavy)

Your retweets

Keywords associated with your command. We know not everyone uses our handle (@USNavy) so we also search

for mentions of Navy, USNavy, #USNavy and U.S. Navy

Campaign or incident-specific keyword searches (e.g., “Navy + collision”)

In a crisis, we adapt and add streams based on how people are talking about the incident. Following both collisions, we

used the hashtags #USSFitzgerald and #USSJohnSMcCain to make it easier to group and track conversations about the

incident, but we also monitored mentions of “Navy + collision.”

When something of this scale happens, it’s best to present one united and informed Navy voice to the public. There will be

a lot of questions. People will dig for information. It’s your job to identify the right voice. Identifying and directing people

to the appropriate spokesperson and online source of information will go a long way to help minimize misinformation.

Step 1: Confirmation of breaking news with link to Navy.mil Step 2: Updates when available

Step 3: Supporting resources to carry the conversation forward

NAVY COMMUNICATORS

19

WWW.NAVY.MIL/SOCIALMEDIA >> U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK

Following each collision, @USNavy was the “digital spokesperson” for the Navy, providing updates for both the media and

affected families. Timely and accurate updates establish trust in your account as an important source of information.

Crisis situations often follow a bell curve. There’s a point where conversations decrease and stabilize. Once that occurs,

there isn’t a need to post minute-by-minute updates, but you should still be an active participant in the conversations.

For weeks following each collision, there were spikes in conversation when new information was released. And there

will still be people wanting more information. Continue to monitor and be ready to direct people to the correct point of

contact for more information on your topic.

Account Security

Official Navy Facebook pages must be attached to individuals’ Facebook profiles. Don’t share a generic Facebook profile;

this frequently leads to commands losing access to their pages. Instead, your designated page administrator will use

his or her personal Facebook account to manually authorize specific Facebook users to manage the official page. The

administrator should grant access to multiple users to minimize the chance of permanently losing access to the page.

Once the individual is granted access, updates to the command’s Facebook page will be posted to the command’s page

and not the individual’s.

What’s often blamed on social media hacking is rooted in poor account management: easy-to-guess passwords;

passwords that aren’t changed periodically or after personnel depart; or lazy device security, such as unlocked computers

or mobile devices. Fortunately, these risks can be mitigated.

Even if your password is strong, adversaries may still be able to gain access to your accounts through weak privacy

options or third-party access. Carefully look at your security options on each platform to minimize the possibility of

unwanted entry. Providing a third-party app or plug-in access to one of your social media accounts can seem like a good

idea, but if one of those third-party apps is compromised, your account likely will be as well. Many of those apps and

plugins are written by unknown third parties who may use them to access your data and friends. Be conservative about

granting third-party apps access, and diligently review who has access to your accounts and eliminate apps you aren’t

familiar with or no longer use.

If you suspect your command’s account has been hijacked or vandalized, follow these steps:

1. Timing is critical in these initial minutes. First, complete a support request through the social media site.

Simultaneously, notify your higher command’s PAO and your command’s security officer. Then, immediately contact

CHINFO. During regular working hours, call Navy Media Content Operations at 703-614-9154. Outside regular working

hours, contact the CHINFO duty officer at 703-850-1047 and request assistance from the digital media team.

2. Change all other social media passwords. Even if you think the security breach is limited to the one account, it’s

prudent to change the passwords of all other social media accounts. If you’ve lost control of other accounts, contact

those platforms immediately as well as CHINFO. You should also change the passwords on your personal accounts.

3. If you don’t have access to your account yet, use other accounts to alert your online community of the breach.

20

U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK >>

The right words and speed matter. Regardless of whether you have access, carefully decide what you’ll say. The

samerules for crisis communication offline apply online. Remember: A traditional 24-hour news cycle offline can

occur in just a few minutes online.

4. Once you’ve regained control of your account, change your password and screen shot the unauthorized content

before deleting it.

Operations Security (OPSEC)

We all know that “Loose Lips Sink Ships,” and social media amplifies OPSEC risks because it enables greater volume and

speed of publicly shared information.

Navy communicators should carefully consider the level of detail when posting information anywhere on the internet,

and they should err on the side of caution. Local procedures should be established to ensure all information posted on

social media is releasable and in accordance with local public affairs guidance and Navy Public Affairs regulations. It’s

then the responsibility of the social media managers to identify and remove information that may compromise OPSEC.

Navy communicators must also inform Sailors, DoN civilians, families and their command’s online community of

OPSEC best practices:

1. Deployment: You should minimize the risk of sharing information related to a current deployment. Instead of saying,

“My Sailor is in ABC unit at DEF camp in GHI city in Afghanistan,” loved ones should rephrase it to: “My Sailor is

deployed.” Close family and friends should already know this information if they’re allowed, so there’s no need to post

it online. Assume that anyone can see any information you post and share regarding your activities, whereabouts

and personal or professional life.

2. Schedules: Posts about scheduled movements and current or future locations should be avoided. “She is coming

home,” should be used instead of, “She will be back on X date from ABC city.” Generally, it’s safer to talk about events

that have happened — not that will happen — unless that information has been released to the media.

3. Personal Information: Limit personal information such as deployment status, addresses, telephone number, location

information, schedules, family members (e.g., names, addresses, birthdates, birthplaces, local towns, schools), etc.

4. Friends: Everyone should be careful who they friend on social media and who follows them. Not everyone who

wants to be a friend or follower is who they claim to be. Be mindful of others attempting to use social presences as

a means of targeting individuals. Only establish and maintain connections with people you know and trust. Review

your connections often.

Other information that should not be shared by anyone includes descriptions of military facilities, unit morale, future

operations or plans, results of operations, technical information, details of weapons systems and equipment status, as

well as the discussion of daily routines and frequently visited locations.

Everyone should be encouraged to post about the following: pride and support for service members, units and specialties;

generalizations about service or duty; port call information after it has been released to the media; general status of the

location of a ship at sea (e.g., operating in the Pacific Ocean, as opposed to off the coast of San Diego); and content from

official Navy social media sites.

NAVY COMMUNICATORS

21

WWW.NAVY.MIL/SOCIALMEDIA >> U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK

Navy social media managers should do the following if they identify OPSEC violations:

1. Record and archive the information, and remove it if possible.

2. Notify the command’s PAO and security officer of any potential OPSEC violation.

3. Inform the user of the OPSEC violation. Use it as a teachable moment and provide them with OPSEC best

practices and resources so they don’t repeat the mistake.

4. Educate the online community about OPSEC, why it’s important and what they can do if they think they know of

a violation.

Political Activity and Endorsements

Navy accounts should only “like” official government social media accounts.

Navy accounts are forbidden from expressing opinions about public issues, including but not limited to politics, political

candidates, elected officials and political parties. Similarly, official Navy accounts should not like or follow partisan

accounts, including but not limited to accounts belonging to a specific political party or political candidate.

The government does not allow solicitations or advertisements of any kind. This includes promotion or endorsement

of any financial, commercial or non-governmental agency. Similarly, attempts to defame or defraud any financial,

commercial or non-governmental agency are prohibited.

Online Advertising

With very few exceptions, Navy accounts may not pay to boost Facebook posts, promote tweets or take similar action

on content.

Navy communicators may not engage in advertisement on social media platforms, websites, apps or any similar venues.

According to the Federal Acquisition Regulation, advertising is defined as “the use of media to promote the sale of

products or services.”

Consult your command’s judge advocate general or contracting officer for exceptions and additional information.

Online Conduct

Any member of the Navy community who experiences or witnesses incidents of improper online behavior should promptly

report it to their chain of command via the Command Managed Equal Opportunity manager or Fleet and Family Support

office. Additional avenues for reporting include Equal Employment Opportunity offices, the Inspector General, Sexual

Assault Prevention and Response offices and the Naval Criminal Investigative Service.

NCIS encourages anyone with knowledge of criminal activity to report it to their local NCIS field office directly or via web

or smartphone app. Specific instructions are available at http://www.ncis.navy.mil/Pages/NCISTips.aspx. Refer to the

handbook’s appendix for additional information.

22

U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK >>

Impersonators

Regularly search for impostors and report them to the social media site.

The impersonation of a senior Navy official, such as a flag officer or a commanding officer, should also be reported to

CHINFO at 703-614-9154 and navysocialmedia@navy.mil.

Ensure your official Navy social media site has been registered as required at http://www.navy.mil/socialmedia. If you

discover a social media site that portrays itself as an official Navy site, contact CHINFO.

Bots

A bot is an automated account run by software capable of posting content or interacting with other users. Some bots

pretend to be humans, while others don’t. Bots are especially prevalent on Twitter.

According to a 2017 Pew Research Center study, 66 percent of tweeted links to popular news and current event websites

were made by suspected bots. This goes up to 89 percent for aggregation sites that collect content from other sites.

In February 2018, Twitter announced changes to its Application Programming Interface that would reduce the ability

of services that allow links and content to be shared across multiple accounts, which would affect bots. However, bots

continue to proliferate on the platform.

Be aware that some bots are part of a botnet, or a network of bots that tweet in a coordinated manner. These bots often

share the same verbatim tweets and sometimes operate to get specific hashtags trending.

Pay attention to the potential indicators of bots:

Anonymity: The less personal information available on account, the more likely it belongs to a bot. Look out for

usernames that seem to contain too many numbers and generic profile photos. Perform a reverse image search

to see if multiple accounts use the same profile photo.

Activity: Bots frequently engage in suspicious activity. A bot account may have only one tweet with a very high

level of engagement or send out a large number of tweets in a short period. Divide the number of tweets by the

number of days the account has been active to see how frequently it posts. According to the Atlantic Council’s

Digital Forensic Research Lab, more than 72 tweets per day is suspicious, and over 144 tweets per day is highly

suspicious.

Amplification: Most bots exist to amplify content. On a typical bot timeline, there will be lots of retweets,

word-for-word copied-and-pasted headlines, and/or shares of news stories without additional comment. There

is little original content on a bot account.

You can report bot accounts on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube. If you’re inundated with comments from

bot accounts on a particular post, consider posting one comment with factual information and a source to dispel

disinformation.

NAVY COMMUNICATORS

23

WWW.NAVY.MIL/SOCIALMEDIA >> U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK

>> SAILORS

Sailors have always been ambassadors of the Navy in their

actions and words, at home and overseas. With that in

mind, it’s important for you to understand what it means

to communicate online to ensure you’re responsibly

representing the Navy.

It’s never been simpler for a Sailor to reach a large, public audience intentionally or unintentionally through email, social

media, blogs and other platforms. While most Sailors don’t work in public affairs nor officially speak on behalf of the

Navy, all Sailors must recognize that they may be perceived as a spokesperson for the Navy simply because they wear

a Navy uniform.

As a Sailor, you’re often the best spokesperson the Navy has; you can share a direct, unfiltered perception of what it means

to serve your country and can provide personal insights into life in the Navy. However, you don’t always have complete

control to decide when you are and are not speaking for the Navy. So, you must understand how to communicate

responsibly as an individual, taking care not to do or say anything to cast yourself or the Navy in a negative or unintended

light.

This handbook will teach you some of the best practices you should follow while using social media.

Online Conduct

No Sailor should communicate on social media or elsewhere in a way that may negatively affect herself or himself or the

Navy. It’s often hard to distinguish between the personal and the professional on the internet, so Sailors should assume

any content they post may affect their personal careers and the reputation of the Navy more broadly. Sailors should not

engage in any conversations or activities that may threaten the Navy’s core values or operational readiness.

Content that is defamatory, threatening, harassing, or discriminatory on the basis of race, color, sex, gender, age, religion,

national origin, sexual orientation or any other protected status is punishable and must be avoided. The internet doesn’t

forget; online habits leave digital footprints. Take caution when posting content, even if you think you’re doing so in a

private, closed community.

Follow the UCMJ

Sailors using social media are subject to the UCMJ and Navy regulations at all times, even when off duty. Commenting,

posting or linking to material that violates the UCMJ may result in administrative or disciplinary action, to include

administrative separation.

Punitive action may include Articles 88, 89, 91, 92, 120b, 120c, 133 or 134 (General Article provisions, Contempt,

Disrespect, Insubordination, Indecent Language, Communicating a threat, Solicitation to commit another Offense,

and Child Pornography offenses), as well as other articles, including Navy Regulations Article 1168, nonconsensual

distribution or broadcast of an intimate image.

24

U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK >> SAILORS

Behaviors with legal consequences include:

Child exploitation/Child sexual exploitation

Computer misuse (hacking)

Cyber stalking

Electronic harassment

Electronic threats

Obscenity

Reporting Incidents

Any member of the Navy community who experiences or witnesses incidents of improper online behavior should

promptly report it to the chain of command via the Command Managed Equal Opportunity manager or Fleet and Family

Support office. Additional avenues for reporting include Equal Employment Opportunity offices, the Inspector General,

Sexual Assault Prevention and Response offices and Naval Criminal Investigative Service. NCIS encourages anyone with

knowledge of criminal activity to report it to their local NCIS field office directly or via web or smartphone app.

Specific instructions are available at http://www.ncis.navy.mil/Pages/NCISTips.aspx. Refer to the handbook’s appendix

for additional information.

Political Activity

Active-duty Sailors may generally express their personal views about public issues or political candidates using social

media — just like they can write a letter to a newspaper editor. If the social media site or content identifies the Sailor

as on active duty (or if they’re reasonably identifiable as an active-duty Sailor), then the content needs to clearly and

prominently state that the views expressed are those of the individual only and not those of the Department of Defense.

However, active-duty service members may not engage in any partisan political activity such as posting or making

direct links to a political party, partisan political candidate, campaign, group or cause. That amounts to distributing

literature on behalf of those entities or individuals, which is prohibited.

Active-duty Sailors can like or follow accounts of a political party or partisan candidate, campaign, group or cause.

However, they cannot suggest that others like, friend or follow them or forward an invitation or solicitation.

Remember, active-duty service members are subject to additional restrictions based on the Joint Ethics Regulation, the

UCMJ and rules about the use of government resources and government communications systems, including email and

internet.

What about Sailors who aren’t on active duty? They’re not subject to the above social media restrictions so long as they

don’t reasonably create the perception or appearance of official sponsorship, approval or endorsement by the DoD or

the Navy.

While additional information is available at https://go.usa.gov/xEEqy, the website and this handbook don’t cover

everything. If in doubt, consult your command’s ethics counselor.

25

WWW.NAVY.MIL/SOCIALMEDIA >> U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK

Cybersecurity

One of the best features of social media sites is the ability to connect people from across the world in spontaneous and

interactive ways. However, this also opens users and their systems to security weaknesses. Information you share on

the internet can provide terrorists, spies and criminals information they may use to harm you or disrupt your command’s

mission. Remember, hacking, configuration errors, social engineering and the sale/sharing of user data mean your

information could become public any time.

You should choose passwords that are unique and difficult to guess for each social media account. You should not share

your passwords or security questions. When using computers, you should make sure to regularly update your anti-virus

software, and beware of links, downloads and attachments. Look for HTTPS://, the lock icon or a green browser bar that

indicate active transmission security before logging in or entering sensitive data (especially when using Wi-Fi hotspots).

Refer to the handbook’s appendix for additional information.

Cyberbullying

While social media sites allow people to connect with loved ones and friends, they also provide new opportunities for

bullying and harassment. Families of Sailors should engage in respectful conduct on social media and report improper

online behavior when appropriate.

According to a study conducted in 2018 by Pew Research Center, 59 percent of teens in the U.S. have personally

experienced abusive behavior online. The most common type of harassment teens encounter online is name-calling

(42 percent). About a third (32 percent) of teens say that someone has spread false rumors about them online, while 21

percent have had someone other than a parent constantly ask where they are, who they’re with or what they’re doing, and

16 percent have been the target of physical threats online.

If you experience bullying or harassment on social media, you can report a user, message or post in-platform. Facebook,

Twitter and Instagram all provide the option of blocking a user. On Facebook, you can report an individual post or

comment by selecting “Give feedback on this post” in the upper right-hand corner of a post or “Give feedback or report

this comment” next to a comment. You can report a tweet by clicking the downward arrow icon and selecting “Report

Tweet.” On Instagram, you can report a post by selecting “Report” in the upper right-hand corner. If someone leaves an

inappropriate comment on your Facebook or Instagram post, you can delete it.

Online bullying, hazing, harassment, stalking, discrimination, retaliation, and any other type of behavior that undermines

dignity and respect are not consistent with Navy core values and negatively impact the force. Any member of the Navy

community experiencing or witnessing incidents of improper online behavior by a Navy community member should

report the activity to their chain of command via the Command Managed Equal Opportunity (CMEO) or Fleet and Family

Support Office.

Operations Security (OPSEC)

We all know that “Loose Lips Sink Ships,” and social media amplifies Operations Security risks because it enables greater

volume and speed of publicly shared information. OPSEC rules are universal and should be maintained online just as

26

U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK >>

they are offline. If you wouldn’t say it, write it or type it, don’t post it on the internet. OPSEC violations commonly occur

when personnel share information with people they don’t know well or if their social media accounts have loose privacy

settings.

As a Sailor, you should follow OPSEC best practices:

1. Deployment: You should minimize the risk of sharing information related to a current deployment. Instead of

saying, “My Sailor is in ABC unit at DEF camp in GHI city in Afghanistan,” loved ones should rephrase it to: “My

Sailor is deployed.” Close family and friends should already know this information if they’re allowed, so there’s no

need to post it online. Assume that anyone can see any information you post and share regarding your activities,

whereabouts, and personal or professional life.

2. Schedules: Posts about scheduled movements and current or future locations should be avoided. “She is coming

home,” should be used instead of saying, “She will be back on X date from ABC city.” Generally, it’s safer to talk about

events that have happened — not that will happen — unless that information has been released to the media.

3. Personal Information: Limit personal information such as deployment status, addresses, telephone number,

location information, schedules, family members (e.g., names, addresses, birthdates, birthplaces, local towns,

schools.), etc.

4. Friends: Everyone should be careful who they friend on social media and who follows them. Not everyone who

wants to be a friend or follower is who they claim to be. Be mindful of others attempting to use social presences as

a means of targeting individuals. Only establish and maintain connections with people you know and trust. Review

your connections often.

Other information that should not be shared by anyone includes descriptions of military facilities, unit morale, future

operations or plans, results of operations, technical information, details of weapons systems, equipment status, daily

routines and frequently visited locations.

You should be careful about who you friend or follow on social media and who friends or follows you. Not everyone who

wants to be your friend or follower is who they claim. Only allow people who you know in real life into your social circles.

Adverse Incidents

Social media is a major part of most people’s lives during good times and bad times. When our shipmates are killed,

wounded or missing in action, it’s hard to control the flow of information distributed through social media platforms.

While it’s difficult to prepare for these situations, it’s important to know that social media can play a role (good or bad) in

the handling of a serious illness, injury or death.

In accordance with DoDI 1300.18, Department of Defense (DoD) Personnel Casualty Matters, Policies and Procedures,

no casualty information on deceased military or DoD civilian personnel may be released to the media or the general

public until 24 hours after notifying the next of kin regarding the casualty status of the member. In the event of a multiple-

loss incident, the start time for the 24-hour period commences upon the notification of the last family member.

SAILORS

27

WWW.NAVY.MIL/SOCIALMEDIA >> U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK

Always follow unit protocol when it comes to these situations. It’s imperative that you don’t add to rumors and speculation.

If approached by someone, state that you don’t know and they should not speculate.

Journalists’ job is to report the news, which includes adverse incidents. The media may look at command, Sailor, DoN

civilian and family members’ social media to get more information. It’s important that privacy settings be regularly

reviewed to be as restrictive as practical. It’s too late when something bad has happened. Should you be contacted by a

member of the media, simply refer them to your command’s public affairs officer.

Private Groups

Closed, private and unlisted social media groups may sound appealing since they appear to offer a sense of privacy.

However, never assume anything on the internet is truly private. The internet doesn’t forget. Content is archived and

traceable forever. Take caution when posting content, even if you think you’re doing so in a private and closed community.

Endorsements

Sailors must not officially endorse or appear to endorse any non-federal entity, event, product, service or enterprise,

including membership drives for organizations and fundraising activities. Additionally, you must never solicit gifts or

prizes for command events in any capacity — on duty, off duty or in a personal capacity.

28

U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK >>

We’re grateful for the dedicated support of families of U.S.

Navy Sailors. One way to support your Sailor is to recognize

the importance of sharing the Navy story — responsibly.

You’ve likely heard that family readiness equals warfighting readiness, and we hope you believe that as strongly as we

do. Without strong, capable families, our Sailors can’t be prepared to do what they must to defend our nation and further

our objectives abroad. Because families are such a big part of our Navy, it’s crucial that should you choose to share your

story, you follow the guidelines to preserve OPSEC and propriety.

This section will teach you some of the best practices that you should follow on social media.

Operations Security (OPSEC)

You might have heard the saying that “Loose Lips Sink Ships” and social media amplifies Operations Security risks

because it enables greater volume and increased speed of information shared publicly. OPSEC violations commonly

occur when someone shares information with people they don’t know well (like their Twitter followers), or if their social

media accounts have loose privacy settings.

Families of Sailors need to be especially careful when it comes to discussing current deployments, scheduled movements,

and current or future locations. Instead of saying, “My son, IT2 Any Sailor, is in Any Unit at Naval Station Anywhere in Any

City, Japan,” you should rephrase it to say, “My Sailor is deployed in the Pacific.” Instead of saying, “My Sailor will be back

in 53 days” you should say “My Sailor is coming home.”

You should also limit the personal information you post about yourself (e.g., names, addresses, birthdates, birthplace,

local towns, schools, etc.) or your Sailor (e.g., deployment status, addresses, telephone number, location information,

schedules, etc.). To be safer, talk about events that have happened — not that will happen unless that information has

been released to the media.

Family members should be careful who they friend or follow on social media and who friends or follows them. Not

everyone who wants to be your friend or follower is who they claim. Only allow people you actually know in real life into

your social circle.

>> FAMILIES

>> DANGEROUS

1) My son, IT2 Any Sailor, is in Any Unit at

Naval Station Anywhere in Any City, Japan.

2) My daughter Ens. Any Sailor, is aboard USS

John C. Stennis. She’s coming home in 53 days.

3) My family is in Houston, Texas.

>> SAFER

1) My Sailor is deployed in the Pacific.

2) My daughter’s ship is coming home in a couple

months.

3) My family is from Texas.

FAMILIES

29

WWW.NAVY.MIL/SOCIALMEDIA >> U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK

As a family member of a Sailor, you should feel free to post about pride and support for service members, port call

information after it has been released to the media, general status of the location of a ship at sea (e.g., operating in the

Pacific Ocean, as opposed to off the coast of San Diego), and posts from official Navy social media presences.

Adverse Incidents

Social media is a major part of most people’s lives during good times and bad times. When Sailors are killed, wounded

or missing in action, it’s hard to control the flow of information distributed through social media platforms. While it’s

difficult to prepare for these situations, it’s important to know that social media can play a role (good or bad) in the

handling of a serious illness, injury or death.

In accordance with DoDI 1300.18, Department of Defense (DoD) Personnel Casualty Matters, Policies and Procedures,

no casualty information on deceased military or DoD civilian personnel may be released to the media or the general

public until 24 hours after notifying the next of kin regarding the casualty status of the member. In the event of a multiple-

loss incident, the start time for the 24-hour period commences upon the notification of the last family member.

It’s imperative that you don’t add to rumors and speculation when there’s a report of an injury or death. If approached by

someone, state that you don’t know and they should not speculate.

Journalists’ job is to report the news, which includes adverse incidents. The media may look at command, Sailor, DoN

civilian and family member social media to get more information. It’s important that privacy settings be regularly reviewed

to be as restrictive as practical. It’s too late when something bad has happened. Should you be contacted by a member

of the media, simply refer them to your command’s public affairs officer.

Cybersecurity

One of the best features of social media sites is the ability to connect people from across the world in spontaneous and

interactive ways. However, this also opens users and their systems to security weaknesses. Information shared on the

internet can provide terrorists, spies and criminals information they can use to harm you or disrupt your command’s

mission. Remember, hacking, configuration errors, social engineering and the sale/sharing of user data mean your

information could become public any time.

Anyone using social media should choose passwords that are unique and difficult to guess for each account. You should

not share passwords or security questions. Regularly update your antivirus software and operating system to install the

latest security patches, and beware of links, downloads and attachments. Look for HTTPS://, the lock icon or a green

browser bar that indicate active transmission security before logging in or entering sensitive data (especially when using

Wi-Fi hotspots).

30

U.S. NAVY SOCIAL MEDIA HANDBOOK >>

Cyberbullying

While social media sites allow people to connect with loved ones and friends, they also provide new opportunities for